During the last twenty years or so, a new batch of historians have examined the nature of what we call Historical Memory. That is to say, these scholars are less concerned with a historical event like the Civil War, though they’re certainly well versed; instead, they they investigate the ways in which future generations remember and frame something like the Civil War.

During the last twenty years or so, a new batch of historians have examined the nature of what we call Historical Memory. That is to say, these scholars are less concerned with a historical event like the Civil War, though they’re certainly well versed; instead, they they investigate the ways in which future generations remember and frame something like the Civil War.

Why focus on the memory of an event instead of the event itself? Because the way a society remembers and presents its history often says quite a bit about that society, if not the actual history.

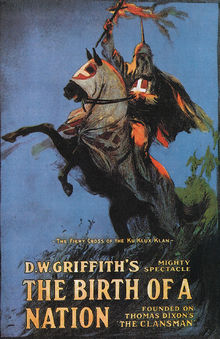

For example, if you watch D.W. Griffith’s blockbuster epic film Birth of a Nation (1915), which is about the Civil War and its aftermath, you won’t learn much at all about the war or the Reconstruction period that followed. To the contrary, you’ll encounter a gross perversion of actual history, a Confederate apologia infected with virulent racism; the KKK are the heroes. Not only is Birth of a Nation overtly offensive to modern sensibilities, but the word “inaccurate” only begins to describe it; the movie is pure propaganda, on a par with Leni Riefenstahl’s pro-Nazi films.

What’s more, historians will tell you, Birth of a Nation is not an isolate. Rather than being a unique manifestation, it captured the zeitgeist of early 20th century America, when the culture was littered with racist commemorations of the Civil War. Historical memories from that period often degraded or erased altogether the role of African Americans, while celebrating the Confederacy’s so-called Lost Cause.

From there Historians connect the dots. It turns out that during the early 20th century, the U.S. was at a high water mark of white supremacist racism, most notably in the form of Jim Crow segregation of blacks, bans on Asian immigration, and the forced assimilation of Indians. Thus, such historical memories helped advance a growing sense of jingoistic nationalism as the U.S. capped off its conquest of Native  nations by expanding across the oceans and conquering places like Hawai’i and the Philippines. To some extent then, though it was ostensibly about the 1860s, Birth of a Nation was helping to usher the birth of an empire during the 1910s.

nations by expanding across the oceans and conquering places like Hawai’i and the Philippines. To some extent then, though it was ostensibly about the 1860s, Birth of a Nation was helping to usher the birth of an empire during the 1910s.

Though I don’t do any research in the area of Historical Memory, lately I’ve been thinking about this approach to history. It’s been exactly a decade since September 11, and commemorations just reached a crescendo. But of course, many of the ways in which Americans have publicly remembered 9/11 say less about the day itself than they do about our current society.

Anyone over the age of twenty certainly has distinct memories of September 11, 2001. That much is true. But the ways in which we choose to express those memories are a product of America in 2011.

Predictably and sadly, much of it has been crass. Many corporations, one way or another, have sought to cash in on those memories. My personal favorite is the State Farm TV commercial that features school children singing Jay-Z’s and Alicia Keys’ “New York: Empire State of Mind”. Watching it makes me feel dirty to think I once bought auto insurance from them.

Others have been more indirect in their exploitation. The New York Times was overwhelming in its rat-a-tat-tat machine gun coverage, spraying readers with stories about 9/11 from every conceivable angle. Meanwhile, 60 Minutes interviewed men and women sickened and traumatized by their work at Ground Zero on September 11 and the months that followed. Even if we assume the best about their intentions, both The Times and 60 Minutes hope to profit handsomely from the historical memories they’re producing and selling.

There were other sorts of public memories, of course, perhaps more genuine, though each complicated in its own way. The federal and most state and local governments all sponsored activities that used 9/11 as a vehicle to celebrate citizenship an d American unity, attitudes that generally advance positive feelings about governments.

d American unity, attitudes that generally advance positive feelings about governments.

Another “official” commemoration was the unveiling of the new 9/11 memorial in lower Manhattan. It’s construction was greatly delayed by political bickering, its location is rife with controversy over its proximity to a proposed Muslim community center, and its architecture, like so many other war memorials since, is clearly influenced by the very successful Vietnam War memorial in Washington, D.C.

And then there were reflections of reflections, such as American Poet Laureate Billy Collins’ new poem, which is not about 9/11 itself, but rather that 9/11 memorial.

Finally, there were organic public commemorations by average, everyday people. Americans came together in a variety of places, ranging from churches to libraries to courthouses, where they earnestly presented solemn memories of mourning and unity, and expressed themselves with silence, candles, flowers, prayers, and in other fashions that the larger society considers appropriate.

Yet none of these really appeal to me.

I’m 43 years old and a native New Yorker, born and raised, 3rd generation Bronx, so I certainly have my memories of that day. But I’m not interested in using this site or any other venue to present them publicly. I have no desire to construct a narrative of that day with the goal of rallying others to my interpretation.

Instead, I’ll tend to my memories privately. Why? Because as a human being, I feel we each have a responsibility to make sense of our lives and histories as best we can.

But as a Historian, I know that to a certain degree, we’re doomed to fail.